After converting to remote work, two independent problems at my work place were brought up: the erosion of the sense of community on our team, and people complaining too much. This seemed absurd — for me, a primary function of a workplace community is to complain. The perfect office happy hour is an exercise in mutual recognition of shitty things that you hate.

An eight-year old boy had never spoken a word. One afternoon, as he sat eating his lunch he turned to his mother and said, “The soup is cold."

His astonished mother exclaimed, “Son, I’ve waited so long to hear you speak. But all these years you never said a thing. Why haven’t you spoken before?"

The boy looked at her and replied, “Up until now, there’s been nothing to complain about.1"

It's clear to me that we get some benefit out of complaining, but the widespread view is that it’s something we begrudgingly have to put up with on occasion, or worse, something that is never ethically permissable. This defense cribs from the only people I found who defend complaint, philosopher Kathryn Norlock2 and psychologist Robin Kowolski3.

Kowalski defines a complaint as "an expression of dissatisfaction, whether subjectively experienced or not, for the purpose of venting emotions or achieving intrapsychic goals, interpersonal goals, or both", which is sufficiently flexible for anything I would consider to be a complaint. Notably, a complaint doesn't need to truthfully reflect the complainer's experience to be a complaint. This is a very broad definition of complaint and includes sometimes overlapping motivations. For the sake of argument, I'll break complaints into 3 subcategories, but one complaint can certainly fall in multiple.

Protesting: Complaining in response to being wronged, which may or may not be constructive

Constructive Complaining: Complaining that strives to improve the situation causing the complainer's dissatisfaction

Kvetching, whining, griping, wailing, etc: A pure expression of dissatisfaction

I suspect most accept protest as a responsibility, constructive complaint as regrettable but sometimes permissible, and griping in any amount as a character flaw. This view forbids (or at least discourages) a lot of valuable complaining. Instead, as Norlock suggests, conceive of skilled complaint in moderation as virtuous. In this view, while yes, it is possible to complain to excess, it's also possible to complain too little. And in some social domains, we often complain too little or possess the wrong moral disposition on complainers.

A selection of people, mostly dudes, complaining about complaining

Is the prevailing view that complaint (other than protest) is undesirable? Anecdotally, I haven't heard much praise for complaining in everyday life. Career and life advice blogs are filled with normative claims that we should complain less.

Complainers are the bane of your boss's existence. Nothing is more irritating or more boring than listening to somebody kvetch about things that they're not willing to change. So never bring up a problem unless you've got a solution to propose-or are willing to take the advice the boss gives you.

Aside: By the way, that whole article is essentially a guide to be maximally subserviant to your boss and has gems like

Regardless of what it says on your job description, your real job is to make your boss successful. There are no exceptions to this rule. None.

There's this for sure misattributed Teddy Roosevelt quote that appears everywhere

Don't forget about the perpetual character assassination of Eeyore.

"Uh-oh! It sounds like a bad case of the Galloping Grumps!" said Christopher Robin.

"The G-Galloping G-Grumps? Is it catching?" worried Piglet.

"Very catching," said Christopher Robin. "Grumpiness and grouchiness gallop quickly from one person to another"

Norlock argues something similar looking at philosophical discourse.

An alien looking at the available philosophical works on complaining might understandably conclude that the great men who enjoin us to never complain have the going account.

Aristotle describes virtues as mean between a vice of excess and deficiency. Confidence is rashness when felt to excess, cowardice when felt to deficiency, and courage (a virtue) when practiced in balance. In this framework, Aristotle sees complaint as some sort of vice, feeling an excess of pain. Aristotle admits complaining is cathartic, "We have our pain lightened when our friends share our distress", and even that it is good to be available for your friend's complaints "it is presumably appropriate to go eagerly, without having to be called, to friends in misfortune". Despite this, on complaining itself, Aristotle is more dour.

Someone with a manly nature tries to prevent his friend from sharing his pain...Females, however, and effeminate men enjoy having people to wail with them; they love them as friends who share their distress. But in everything we clearly must imitate the better person.

Ignoring the giant yikes in the room for a second, an interesting point is that Aristotle doesn't find complaint fruitless, but claims we should still avoid it because it benefits us and hurts our friends. Even if you grant you shouldn't complain in cases where that's true (which, meh), the view of complaint as a zero-sum game seems to not capture many complaint interactions in practice. When a complaint is shared by both parties, both may benefit. Nor does commiseration require negative emotions.

The stoics say you should just accept anything out of your control, "If you see anybody wail and complain, call him a slave."4 Kant's in the same ballpark, "Complaining and whimpering, even crying out in bodily pain, are unworthy of you, and most of all when you are aware that you deserve pain." Nietzsche would no doubt attribute complaints to ressentiment, mean-spirited attempts to moralize and blame, stemming from an inability to affect real change.

So complaining is a bad habit, a deep character flaw driven by weakness or impotence to be repressed. Rather than complain you should man up; Norlock also argues that the gendered critique of complaint continues past Aristotle as well. Then the anti-complaint norm is especially damaging to women, whether it be because women "complain more" or because women are perceived to complain more doesn't especially matter.

The result is both that “complaining is bad” and that women are associated with complaining. This sentiment is embodied in the title quote of Linda Perriton's discussion of language in the corporate discourse, "We Don’t Want Complaining Women!”5 . The damage isn't restricted to only women though; the argument against complaining begins to read as against feeling as a whole, something that's at odds with practical well-being.

Distinguishing Constructive Complaints

If you buy into the prevailing view and want to forbid non-constructive complaining, you'll be tempted to say things like fake Teddy Roosevelt: "If you have to make a complaint, at least provide a solution". I've heard this in corporate settings, and this is a dumb thing to say even if you really do want to eliminate all kvetching (which I will argue is also a dumb thing to want). This eliminates a class of no-brainer good complaints: one where the complainer doesn't know the solution but it happens to be readily available to the complainee. This is a common occurrence in software, it's a straightforward way to propagate informal productivity practices: Bob complains about having to log into machines one by one, Alice points him to ssh multiplexers.

A less obvious downside is that presenting a solution takes effort. It may not be worth it to develop a solution if the complaint is not felt by any peers. Presenting solutions with the problem might also lead to worse overall solutions than if turned over to the group. Tying the proposed solution and the complaint together can incorrectly couple them (a variant of the XY problem)— if Alice hates X and provides one way to solve X with Y, she may rephrase her complaint from "I'm sick of X" (good), to "I'm sick of not Y" (which is fine if Y is the best way to solve X, but it may not be). Complaints without solutions communicate data that can improve the inputs to the problem-solving process. For similar reasons, experimental psychologist Norman R.F. Maier suggests virtually the opposite approach6.

Norman R. F. Maier noted that when a group faces a problem, the natural tendency of its members is to propose possible solutions as they begin to discuss the problem. Consequently, the group interaction focuses on the merits and problems of the proposed solutions, people become emotionally attached to the ones they have suggested, and superior solutions are not suggested. Maier enacted an edict to enhance group problem solving: “Do not propose solutions until the problem has been discussed as thoroughly as possible without suggesting any.” It is easy to show that this edict works in contexts where there are objectively defined good solutions to problems.

A refinement might be "If you have to make a complaint, make sure the problem is solvable". This isn't much better. Most problems relevant to an organization are solvable in some sense, the salient criterion is usually whether it is practical to do so. As with the previous formulation, it's important to figure out whether the problem is worth solving, something the complaint helps you figure out.

It's clear then that complaints may communicate information useful for problem-solving. This holds even when the content of the complaint is already known to all parties. If Alice and Bob both individually know Aunt Carol is a bad cook, before a complaint they know only that they know it. After, Alice knows Bob knows, and knows Bob knows that she knows, etc. The complaint converts mutual knowledge (knowledge all parties have) into common knowledge (knowledge that all parties have the knowledge). Common knowledge is a requirement for successful social coordination, so Bob can propose to Alice that they grab a pizza before heading to their aunt's house.

An overly utilitarian definition of "constructive" would be any complaint that leaves the world in a "better" state. This is a useless definition in the other direction — it's of course tautologically good to only allow constructive complaints. Further, it would be impossible to discuss the goodness or badness of a kvetch because a good complaint would become constructive by definition. A better definition is "a complaint that may improve the situation causing the complainer's dissatisfaction". So Bob complaining about the rain is a kvetch, but Bob complaining about Alice's sprinklers to her is a constructive complaint. Even if complaining about the rain makes Bob feels better it doesn't improve the situation (nor should Bob have any hope that it might) so it's not constructive.

"May" does a lot of work in this definition, because we should allow complaints where we don't yet know if it will produce improvement in the condition. Alternatively, the definition could hinge on the outcome of the complaint; after the complaint is leveled it can be determined whether or not it led to constructive action. Conceptually this is fine, but it's not at all helpful for any normative work because you cannot determine whether it was appropriate to make the complaint until after you make it (and even then it may not be clear). The result is that a more permissive conception of what is constructive is required to make full use of the problem-solving utility of complaint.

Kvetching is fine actually

What about kvetching, griping, whining — complaining without any concrete intention of a solution? In admitting that it doesn't solve anything, must it be condemned to the trash heap of other indefensible human compulsions, even if helps us personally? No one likes the chronic complainer, but I'd gladly wallow with them in a pool of suffering than with a Panglossian optimist who tried to assure me that the pool was half full (half-empty? hard to tell when the liquid is misery).

So far, this has been a mostly business case style argument that complaint's role in problem-solving is undervalued. It's wise to drop the language of "the business case" at this point; though one may argue that kvetching, in the same way as other virtues like honesty, is good to practice for the profit of an organization, this seems to be a glib view of virtue. Let's just assume we want the people around us to have a good character regardless of any profit motive.

There is some common knowledge of the downsides of complaint to excess. Kowalski lists well-known negatives of complaint: ostracism from peers, increased personal feelings of negativity, and a mood contagion effect (the galloping grumps). So if everyone thinks complaining is toxic, why does everyone do it all the time?

Complaining feels good. Not every complaint, but on the whole, people complain because it's a means of catharsis. This is even with the perceived negatives of having to complain in the first place — I feel a little bad that I have exhibited a weakness of character and subjected my friend to a complaint, but the relief from the complaint makes it worth it.

Kowolski compiles a long list of claims that people who fail to complain when they need to experience worse psychological outcomes7.

People who inhibit expressing their dissatisfaction often ruminate about the problem, blowing their dissatisfaction out of proportion (Wgener, Schneider, Carter, & White)

…

As noted by Pennebaker (1990, 1993), the failure to reveal troubling or traumatic information takes psychological and physiological work, resulting in impaired psychological and physical functioning

…

Infrequent complainers also at heightened risk for depression relative to more frequent complainers (Folkman & Lazarus, 1986)

So if griping cultivates a better personal and societal outcome at least sometimes, then a draconian prohibition on all griping is ill-conceived.

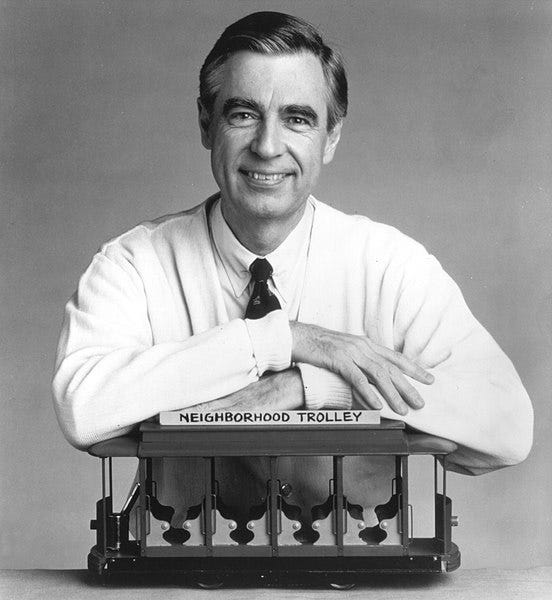

In the wisdom of philosopher Fred Rogers.

“Anything that's human is mentionable, and anything that is mentionable can be more manageable. When we can talk about our feelings, they become less overwhelming, less upsetting, and less scary. The people we trust with that important talk can help us know that we are not alone.”

The complaint by itself may provide relief, but when the complaint receives commiseration, it's validating. If we consider a subjective state of self-doubt and isolation itself to be a vice, where we're unsure if our experience is valid and if our problems are real, it's plausible to attribute this to a deficiency of complaint. Likewise, that means offering commiseration to others in a state of isolation through complaint is also desirable. Norlock uses the example of co-workers being soaked in the rain — to ignore their shared mutual pain misses the opportunity for good.

[I]nstead of seeming “soft,” the coworker who offers the negative thought about the discomfort due to the rain seems alert and attentive to a shared state. Seeing another soaked through provides an opportunity to complain in order to commiserate, opening a door for agreement and connection.

Aside: Power and Complaint

I'm embedding an assumption, especially for the workplace, that promoting communication and mental well-being is a goal of the organization. Naively, leaders of organizations discourage complaints because they under-value the positive effects, and these are just mistakes in the cost-benefit calculus. Since they either want to promote well-being as an end of itself, or they think mental well-being will improve the organizational bottom line (profit), arguing that complaint is undervalued could conceivably change their behavior.

This is an overly rosy view. Those same qualities that complaint promotes could enable a self-reflective workforce that questions organizational authority. On the cynical view, rather than a misunderstanding that is producing a suboptimal work environment, complaint moratoriums are strategic ploys to keep workers isolated. Limiting complaint implicitly or explicitly is exerting control over the space of discourse, making it less likely for common worker goals to be identified and acted upon.

One way to limit complaint is to make it illegal! 8

If workers were allowed to congregate together, they would compare injustices, scheme and conspire, foment revolutionary intrigues. Thus, laws like those of 1838 in France came into being which forbade public discussion between work peers, and a system of spies was set up in the city to report on where the little molecules of laborers congregated—in which cafes, at which times

A less easy way is to establish a set of social mores discouraging complaint, but it can be understood as working to similar ends. From the perspective of the powerful, social cohesion and mutual recognition are dangerous. Then workers or peers in an organization need to be suspicious of hostility to complaint. This hostility can come from the working peers themselves because anti-complaint preferences are firmly rooted in broader society. Nevertheless, this hostility still puts limits on channels of communication between peers. Attacks on complaining are attacks on the lateral bonds that keep peers in solidarity, and the standard Marxist arguments for why we should avoid being potatoes in a sack apply 9.

The small-holding peasants form an enormous mass whose members live in similar conditions but without entering into manifold relations with each other. Their mode of production isolates them from one another instead of bringing them into mutual intercourse.... Thus the great mass of the French nation is formed by the simple addition of homologous magnitudes, much as potatoes in a sack form a sack of potatoes.

Or as Foucault says, “solitude is the primary condition of total submission”. Social isolation might be weaker than physical solitude, but if complaint is part of a balanced diet of solidarity, workers should fight to keep this domain of discourse. And workers do, take this interesting bit from Sennet who argues the public story for gatherings of workers were sometimes a disguise 10.

In order to shield themselves, workers began to pretend that their get-togethers in cafes were only for the purpose of heavy and sustained drinking after the day's labor. The expression boire un litre ("drink a liter" of wine) came in the 1840's into usage among workers; it meant, loudly declaimed in the hearing of the employer, that the boys were going to lose themselves in drink at the cafe. There is nothing to fear from their sociability; drink will have rendered them speechless.

So in some sense, it's dumb for me to argue that workplace leadership should promote complaint when it contradicts11 the bourgeois ethos or whatever. In reality though, even if some of the negative views of complaint have a machiavellian origin, to claim all distaste of complaint derives from maintenance of power structures is conspiratorial thinking.

It's still practical to argue that adjusting the slider to more complaint may produce better outcomes to those in positions of power, especially for those who believe emotional well-being is aligned with organizational goals. If we suppose there are people with organizational power that support complaint for altruistic reasons, how does power affect how we should complain? Much of this discussion involves the exchange of complaint and commiseration between equals, an unequal distribution of organizational power needs additional considerations.

Complaints going up the hierarchy are especially precarious for the complainer. Fear of retribution seems justified. A weirder problem, that complaint between equals is usually impotent (oof, more gendered language) can be considered a feature. By default, a complaint to an equal is probably just an exchange of information and validation. Any actions taken as a result will probably be discussed by both parties. But when complaints go upward, it's also possible that the recipient feels a duty to use their power to act on this complaint. Concretely, this is the danger when Alice complains to Carol about Bob to let off steam, but instead, Carol fires Bob. Dealing with this is easy if you can remember though: the complainer should take care to specify their complaints, the recipient should discuss any actions with the complainer before taking them.

The other direction is similarly fraught. Complaints downward will inevitably be viewed as edicts or orders, and be given more weight than complaints from peers.

More fundamentally, complaint as a channel for communication is compromised by inequality. Participants are encouraged to strategically present their position, it’s not the ideal speech situation (not that it ever is). Specifically, complaint in the upward direction is less authentic because it often attempts to affirm what the superior wants to hear. What Marx calls “the dull compulsion of economic relations” is enough to coerce misrepresentation – a subordinate is more interested in keeping their job than revealing the truth. Or as Hagbard Celine's second law says, "communication occurs only between equals"12.

That said, the role of an organizational leader who promotes complaint is less to participate in complaint across many levels of hierarchy, but instead to encourage it between peers. Which just means not publicly chastising or discouraging complaint, and allowing open forums for honest communication between peers.

Virtuous Complaining

There's no arguing that people complain too much sometimes. I haven't bothered listing the dangers of complaint to excess, because everyone already knows them. But, ideally, I've established that it's also possible to complain too little, and so it's sometimes appropriate to skillfully complain. While even without more specifics this might change how you judge complaints, it's unclear what it means to skillfully complain. To be honest, I'm not sure either.

The discussion so far suggests some attributes of the form of skilled complaints. For one, prefacing complaints with "I hate to complain" or "Sorry to complain" again frames the complaint as indulging in a vice, which continues to stigmatize complaint. If this is a skillful complaint, presenting complaints without the moralizing encourages correct complaining. The ideal complaint is also commiserated, so all else being equal, it's likely better to complain when a mutual understanding of the dissatisfaction is possible. I don't think this should be taken too far, as complaining about a work problem to an uninvolved friend might serve a different need than a co-worker experiencing the same issue — from the friend comes a general validation that your problems are real, from the co-worker comes a specific validation that the issue itself is real.

Since many of the functions of complaining are around validation and establishing common knowledge, it's worth internalizing that skillful receipt of complaint doesn't require much more than listening. Complaints aren't necessarily invitations for advice, it's now clear that they serve other functions. Probably best to ask if your advice is wanted before offering it.

This still leaves the difficult questions of what is appropriate to complain about, and when is it appropriate to complain. Norlock suggests one uncontroversial criterion for what — only complain if you mean it. An insincere complaint takes on both the problems of inauthenticity and the potential negative effects of complaint as well. As for when, maybe the right approach is to consider qualities that arise in communities in both vices of deficiency and excess of complaint.

Since we guess that a good complaint improves solidarity, a deficiency of complaint likely promotes isolation. An excess provokes anxiety and hostility. Maybe a relatable framing is looking at digital spaces. After seeing the ninth beach vacation picture, you might start to feel alone in your problem of not being on the beach. After reading your thousandth moral outrage tweet, you might find yourself in a negativity spiral. These should push you to more or less complaining to arrive at a virtuous mean.

Complain Some

Complaints are often more constructive than organizations want to give them credit for, it's hard to determine whether they are constructive until they are leveled, and even when they aren't they still serve an important interpersonal function that itself may be worth it.

For constructive complaint, broaden your view. Complaints are data. Err on the side of flexibility, it's easier to throw out data that is not actionable than to fully fail to see a problem exists.

For kvetching, embrace the expression of subjective experience in yourself and others. Realize that validation is an end by itself.

I don't know if anyone really knows how to skillfully complain, but I reject the notion that we should never complain.

Kathyrn Norlock, Can’t Complain . Which I’d generally recommend reading if anything in this post was interesting to you.

Robin M Kowalski. Whining, Griping, and Complaining: Positivity in the Negativity .

Epictetus, D4.1, but really just go to any one of those stoic quote of the day mills for bunch of variants on this

Linda Perriton, “We Don’t Want Complaining Women!” A Critical Analysis of the Business Case for Diversity. This case seems especially interesting in that the “complaining” in this case is arguing for gender equality. The reduction of the discussion to “complaining”, is an attempt to depoliticize diversity discourse. Incidentally, it's also a good incarnation of a cat coupling (women who happen to complain / women because they complain).

Robyn M. Dawes, Rational Choice in An Uncertain World, p. 55-56

There’s a lot of evidence presented in Kowalski not produced here. It’s probably worth taking the standard grain of salt with these results, but there’s also probably too much here to dismiss all of the potential positive effects of complaining. Regardless if studies actually capture the positive effects, these at least offer plausible mechanisms for psychological benefits.

Richard Sennett, The Fall of Public Man, p. 215

Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Marx’s thoughts on the barriers to class consciousness among peasants in 1850s France.

Also from The Fall of Public Man, but examples of laborers or oppressed classes preserving their spaces, and the importance of doing so, are a dime a dozen. For my money, a good discussion is James C. Scott’s Domination and the Arts of Resistance , particularly the chapter Making Social Space for a Dissident Subculture.

This is already getting quite winded, but it’s sometimes proposed that elites allow minor complaint and protest as a sort of safety valve — something that lets off steam without challenging the status quo. Can also see Domination and the Arts of Resistance p. 185 for a discussion but long story short I don’t really buy it.

From Never Whistle While You're Pissing a book by fictional weirdo Hagbard Celine within The Illuminatus Triology by real life weirdo Robert Anton Wilson

> your real job is to make your boss successful

Even if you go maximally cynical then your job is to make your boss happy (about you), not successful.

In many cases optimal cynical self-interested strategy does not require boss to be successful, as there would be too stupid to appreciate what is happening :)