A $795M analogy

Locast, broadcast copyright, and the fall of big antenna

A few weeks ago a federal court ruled that Locast, a non-profit that streams over the air television stations through the internet, was not protected by a copyright exemption for non-commercial entities. Locast has ceased operations for the time being.

But Locast is only the latest episode in a decades-long struggle to adapt existing copyright statutes to the internet. It has produced an industry that stores exabytes of data no one needs, plagued by disputes over how much to pay for free content. Locast and its precursors, Cartoon Network v. Cablevision and ABC v. Aereo, highlight the problem.

Broadcast cases are weird. Lawyers and lobbyists compare systems that manage information to parking lots, valets, the Boston strangler, “Pac-Man gulping everything in sight”, phonograph record copying, copy shops, copy shops that let you operate the copy machine on their premises, copy shops that let you operate the copy machine on their premises and provide you with a library card, a VCR with mile long cord, and the portrait of Dorian Gray.

Worse, these cases have become the legal foundation of the modern cloud storage industry. How did we end up with a set of imprecise analogies for digital information that wastes 1.4 million metric tons of Co2 a year?

I am not a lawyer1 .

1

In 2006, cable operator Cablevision launches a cloud DVR service. Copyright holders claim that this system reproduces and performs their content but only pays to transmit it.

In the Sony Betamax case, courts found that VCR manufacturers were not liable for home recordings that may infringe on copyrights. So Cablevision thinks, OK, we'll do the exact same thing but we'll hold on to your DVR for you in our warehouse. Cablevision's position is that they just make DVRs with a longer cord.

To the consumer, the Cablevision DVR looks like a menu of content you can play, provided you remembered to record it. However, Cablevision only pays for a retransmission license. Like any other cable operator, they send streams from networks to homes through wires. But if a customer marks a program in that stream for recording, Cablevision stores a unique copy for that specific customer on "their" DVR. The customer can do whatever they want with their copy, as they could for a home DVR recording.

Networks sue Cablevision for 3 things.

They split and buffer the broadcast stream before making copies for users, constituting an unauthorized reproduction

They make the copy to the user’s DVR, another unauthorized reproduction

They transmit the work when the user requests it, constituting an unauthorized public performance

The court dismisses the first claim, but the ruling might mean if you buffer data in RAM for much longer than 1.2 seconds, you could become liable for infringement2. The second claim fails because it is the user who is making the copy, not Cablevision. Even though the copy process is complex, it is fully automated and at the user’s discretion. Cablevision is more like… self-service at a Kinkos?

Cablevision more closely resembles a store proprietor who charges customers to use a photocopier on his premises, and it seems incorrect to say, without more, that such a proprietor "makes" any copies when his machines are actually operated by his customers.

The final claim is dismissed because the playback is from unique copies, so it does not meet the requirements of a public performance. The court specifies that if the playback had come from a single copy, it would have.

Cablevision wins their case. Which is great! It’s a broader interpretation of private performance and fair use for consumers. It opens up options for cloud innovators. If it went the other way, cloud storage services like dropbox might not exist — every time you accessed a personal copy of a copyrighted work on Dropbox they could be infringing on copyright. Enterprise storage and compute providers like Amazon and Google would have the same issue.

It’s safe to treat cloud DVRs as DVRs with really long cords. And we're forced to accept the weird implications of that.

2

The weird implications of that:

So Cablevision was legal because they stored a unique copy of content for every user who records it. Every user. If 10 million people record the Game of Thrones finale, Cablevision would store 10 million identical copies.

This is insane, right? Bits are bits, I cannot distinguish whether you give me back “my” Game of Thrones bits or someone else’s. Even so, any conservative provider of a cloud DVR service probably still adheres to the Cablevision model3. In all likelihood, if you have a cloud DVR at home and you record something, you'll end up making a redundant copy of the content in some data center.

Let's do some wildly speculative and irresponsible calculation.

Suppose cloud DVR operators are storing 1080P source content with a bitrate of 6Mbps. Let’s say they support 90 channels, provide users with 200 hours of content storage, and there are about 25 million cloud DVR subscribers.4

If the world made sense, we’d just need 1 copy of every program. Say recordings only go back 10 years. Worst case, 10 years of 90 channels at 6Mbps is a “paltry” 21.3 petabytes.

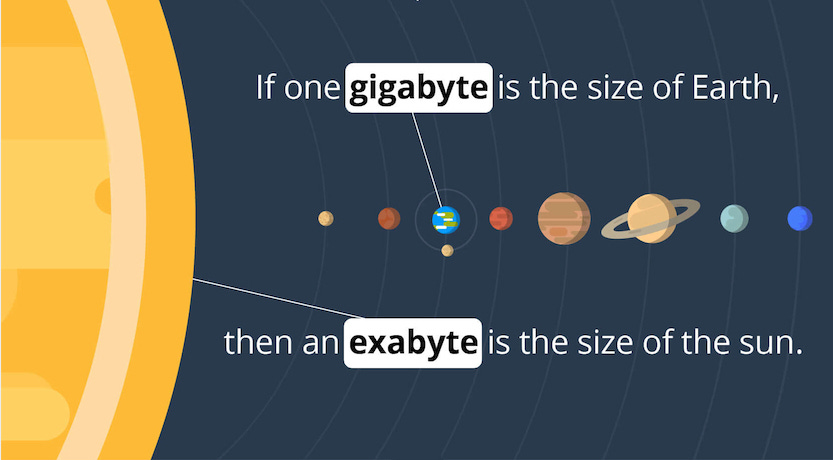

But since the world doesn’t make sense, 200 hours at 6Mbps for each of the 25 million users is 13.5 exabytes of data. With redundancy and availability overhead, it’s more like 15.9 exabytes5 . This is a mind boggling amount of storage. It’s 600 times more than the “ideal-world” storage requirement.

It’s about 2 million 8TB hard drives. If you vertically stacked them, they’d reach outer space and back 3 times. It’s about $795 million6 in initial hardware costs. You’d expect 50 drives to fail every day, enough to employ 5 people full-time to replace them7. Powering all this storage takes something like 2 billion kWh8 per year. That’s 1.4 million metric tons of CO2 9, just behind Malta. The power alone is $217 million10 per year.

AARGH, BITS ARE BITS! We're producing enough carbon a year to power a small country to meet a narrow definition of private performance. Who does this even help? It doesn’t benefit copyright holders — you can still make reproductions and performances but you just have to burn a pile of money to do so. There must be a workaround!

What if the storage system the DVRs use supports deduplication? Before you upload your file, you compute a hash of it. It's like a fingerprint, something much smaller than the original file that uniquely identifies it (more or less). If the hash of the file matches an existing file, the system can just point to that existing file instead of making a new copy of it. Dropbox originally had some form of global deduplication like this.

Probably illegal11.

Okay, but that’s weird because deduplication can be more subtle than that. Some filesystems support deduplication — btrfs can deduplicate blocks (4KiB chunks of the file). So co-locating any copies of the same content on the same hard drive will effectively only store it once. If this isn’t acceptable, a misformatted hard drive could make you guilty of copyright infringement.

Even worse. Is compression deduplication? If you store content on disks that support hardware compression (e.g. the Sandforce SSD controller, the Seagate Nytro 1000 series), you’ll effectively be serving multiple user’s content from the same on-disk bits. If this isn’t acceptable, just picking the wrong drive makes you a copyright infringer.

Even even worse. Disks aren’t the only place that compression can be inserted. MacOS, for example, may choose to compress memory that’s not in use to avoid swapping. Imagine the system has loaded the same content for two users from two distinct on-disk sources into RAM. With compression the system may serve both users from the same in-memory bits. And although hardware compression in the DRAM itself hasn’t caught on, the idea has been around for a while. If this isn’t acceptable, deduplicating bytes anywhere in your stack might be copyright infringement.

All unclear. Start a company, get sued, and report back.

3

Aereo, founded in 2012, was a service that let users watch over the air networks live or timeshifted over the internet. I’m like 90% sure the founding was this:

Here’s Aereo's plan. Cablevision's model held up in federal court, and moreover, is essential for cloud services. Cablevision distributed content with only a license to transmit. Well, Aereo does the exact same thing, but instead of piggybacking on licensed content like Cablevision did, they don’t pay for any licenses. Instead, if you pay for Aereo's service, you get your own tiny antenna in their nearby data center. You can then access over the air (OTA) broadcast content12 through the internet. It's your content since it's your antenna, so Aereo argues that it is a private performance in the same sense that Cablevision was. In the court’s previous language of “copy machines”, Aereo is “a copy shop that provides its patrons with a library card”.

Okay, so what’s the big deal? The FCC gives free licenses to a finite spectrum resource to broadcast stations. In return, stations should air free content in the “public interest.” OTA content is supposed to be free anyway, if anything this smooths out areas with weak signals but good internet. And the ads in the content should get more eyeballs, seems like a win-win.

Broadcast networks and stations don’t like this. Broadcast stations make a lot of their money (In 2019, $11.72 billion, 35% of their total revenue) charging pay cable operators to carry broadcast programming. Of course, cable operators are totally into Aereo — they are in constant negotiation with broadcasters over these retransmission fees, sometimes leading them to drop local networks. If Aereo works, cable operators can make their own fantastical antenna emporiums. And I bet antenna manufactures love it too.

So the broadcasters sue Aereo, and it eventually makes it to the supreme court.

Aereo’s loophole is clever (well, not that clever, given the outcome). It's hard to say what Aereo does is illegal without saying what Dropbox does is too. A lot of the court’s questions are effectively "Look, I'd love to rule in your favor. But you've got to convince me I'm not going to accidentally make google illegal".

JUSTICE ALITO: [...] So maybe you could explain to me what is the difference, in your view, between what Aereo does and a remote storage DVR system [...].

MR. CLEMENT: I think the potential difference, and it's both the CloudLocker storage and this example, I don't think this Court has to decide it today. I think it can just be confident they are different. Here is the --

JUSTICE ALITO: Well, I don't find that very satisfying because I really -- I need to know how far the rationale that you want us to accept will go, and I need to understand, I think, what effect it will have on these other technologies.

Particularly great is this increasingly frustrated line of questions where the court is really trying to get Aereo to admit that they are totally built around this exploiting this loophole.

CHEIF JUSTICE ROBERTS: I mean, there's no technological reason for you to have 10,000 dimesized antenna, other than to get around the copyright laws.

[rationalization of antennas]

CHIEF JUSTICE SCALIA: But his question is, is there any reason you did it other than not to violate the copyright laws?

[rationalization intensifies]

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: All I'm trying to get at, and I'm not saying it's outcome determinative or necessarily bad, I'm just saying your technological model is based solely on circumventing legal prohibitions that you don't want to comply with, which is fine. I mean, that's you know, lawyers do that.

The court rules against Aereo 6-3. I originally thought the strangeness of digital copyright outcomes reflected a lack of technical literacy in the courts. But for the most part, I find the Aereo discussion shows general digital competency, and an appropriate aesthetic disgust for the “identical bits are different” problem.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: That's just saying your copy is different from my copy.

MR. FREDERICK: Correct.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: But that's the reason we call them copies, because they're the same.

Instead, the argument hinges on the congressional intent of a 1976 amendment to the copyright act: the court had decided cable retransmission did not constitute infringement, so congress specifically brought cable operators into the scope of the act. Externally, if you squint, Aereo looks like a cable operator, so probably congress would have wanted this law to apply to them. In the dissent, Scalia argues that any reasonable looks-like-a-cable-provider criteria could be applied to cloud DVRs as well, thus potentially rendering cloud DVR use (and consequently, all cloud storage) infringing public performance.

The Court vows that its ruling will not affect cloud-storage providers and cable- television systems […] but it cannot deliver on that promise given the imprecision of its result-driven rule.

The majority opinion is that Aereo might endanger a business model that congress thought was worth preserving 45 years ago. Back then, the FCC was described as having assumed a “veritable Kama Sutra of regulatory positions” (nice). Since then the underlying technical situation has only become more complex. That Aereo should fall into the cable operator bucket hardly seems open and shut. Modern legislators should decide whether they want these rights protected in light of the changes in the television industry and the internet.

More cynically, Aereo lost because of a notion that broadcasters were entitled to this revenue stream, independent of changes in technology. And now, we have an elusive ad-hoc criterion that can be used to keep out the innovation that disrupts entrenched systems, without making google illegal. From Scalia’s dissent:

It will take years, perhaps decades, to determine which automated systems now in existence are governed by the traditional volitional-conduct test and which get the Aereo treatment. (And automated systems now in contemplation will have to take their chances.)

4

Locast, launched in 2018, is a non-profit that lets users watch OTA networks over the internet.

This time I don’t even have to speculate about a loophole origin story. David Goodfriend conceived Locast while lecturing on Aereo at Georgetown Law.

Goodfriend surmised that a non-profit organization would be exempt from the provision; Locast became his proof of concept.

Locast does pretty much the same thing as Aereo, but takes advantage of an exemption from copyright granted to non-profits. Goodfriend frames the mission more bombastically:

“The American people have given you something really valuable, the airways, for free,” he said, talking about the broadcasters, his eyes popping at the word “free.” Slowing down for emphasis, he added: “So shouldn’t we get something back for free? Which is great television. That’s the social contract, right?”

Though Goodfriend has a name seemingly engineered to avoid suspicion, it’s good to be cognizant that he’s a former Dish network exec when evaluating all that “public good” rhetoric. And although Locast is “free”, it does interrupt you every 15 minutes unless you sign on for a $5 monthly donation. Nevertheless, I am generally annoyed that I have to fiddle with a dumb antenna to get barely functional access that is supposed to be my end of the spectrum bargain.

For a while, Locast goes unchallenged. When local broadcast retransmission negotiation goes bad, some operators take to directing their customers to download Locast, a modern version of mailing antennas to their customers.

In 2019, broadcasters team up to sue Locast, surprising no one. In a fun twist, Locast also countersues broadcasters for anti-competitive conspiracy to restrain trade. They claim broadcasters purposely hobble OTA signals to encourage the use of pay-for-tv access to local content:

The broadcasters have colluded to limit practical access to the over-the-air signals by broadcasting signals that they know are of insufficient strength to be accessed by all members of the public within the relevant local geographic areas. Mr. Goodfriend has spoken with a representative from a major market participant who indicated that he had been told by vendors of transmitter equipment that the broadcasters intentionally purchase low-end equipment even though other equipment is available for sale that could provide better over-the-air coverage.

And that broadcasters have been intimidating Locast’s potential partners:

During a meeting between a senior executive at T-Mobile and Mr. Goodfriend on December 4, 2018, in Denver, Colorado, the executive recounted that he was at a group gathering where a broadcast industry representative said that they would crush Locast.

[…] the executive said that two entities—one broadcast owner and another broadcast network—said that they were waiting on Locast to get bigger and then would sue Locast and any supporters.

[…] In a meeting between representatives of SFCNY and senior executives at YouTubeTV in April 2019, the executives indicated that they had been told that if YouTubeTV provides access to Locast, then YouTubeTV will be punished by the Big 4 broadcasters in negotiating carriage agreements for other non-broadcast programming channels.

Are claims always this gossipy?

Anyways, the broadcasters and Locast request summary judgments, which brings us to the present. SDNY rules against Locast, claiming the organization doesn’t meet the non-commercial requirements of the copyright exemption.

Since portions of its user payments fund Locast's expansion, its charges exceed those "necessary to defray the actual and reasonable costs of maintaining and operating the secondary transmission service", which is the only exemption granted in Section 111 (a) (5).

I don’t really know if this is fair or not. On one hand, Locast doesn’t seem that non-commercial considering the product is only practically usable if you pay. On the other hand, the ruling indicates that the use of user payments for “expansion” of the service does not qualify for a copyright exemption, which seems to make it difficult for any entity to qualify.

Since congress included this exemption, presumably there is some way to qualify for it, otherwise it wouldn’t exist. So the non-profit “loophole” still hasn’t been closed. Even if Locast doesn’t bother to appeal, there’s nothing to stop an entity that meets the copyright exemption requirements from rerunning Locast’s play. And given large cable operators may have a strong interest in bankrolling such an entity, it seems likely to happen.

5

From MPAA president Jack Valenti’s 1982 testimony to congress, on the VCR:

But now we are facing a very new and a very troubling assault on our fiscal security, on our very economic life and we are facing it from a thing called the video cassette recorder and its necessary companion called the blank tape. And it is like a great tidal wave just off the shore.

[…] We are going to bleed and bleed and hemorrhage, unless this Congress at least protects one industry that is able to retrieve a surplus balance of trade and whose total future depends on its protection from the savagery and the ravages of this machine [the VCR].

[…] I say to you that the VCR is to the American film producer and the American public as the Boston strangler is to the woman home alone.

And yes, all of Valenti’s testimony is similarly bonkers. Luckily, congress chose not to impose royalties for VCRs or video rental. 4 years after Jack Valenti compared the VCR to the Boston strangler, “videocassettes became the motion picture industry’s largest source of revenue.”

After Aereo/Locast, internet re-transmission of free OTA content is in pretty rough shape. Because Aereo looks too much like a cable company, its transmissions are public performance. Because Aereo doesn’t look enough like a cable company, it can’t use the regulatory apparatus for licensing that traditional cable companies use. But all these companies do is take the local signal that is always available over the air (but might not be coming in strong for you for a million practical reasons) and deliver it over a more widely available medium.

Cablevision’s ruling was “good” because it took a permissive approach to copyright and in that loophole, an important industry arose. But it was also “bad” because it makes us do things that don’t make sense. Aereo/Locast’s rulings are “bad” because they kill a fundamentally useful technology, destroying public value. But they’re “good” in that they didn’t create a useless teensy antenna industry.

So where does that leave us? The good news is: copyright is not a right, and intellectual property is not property. That is to say, copyright holders don’t have any natural rights in the Lockean sense. Instead, copyright is consequentialist — an incentive to enrich the public, “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.” This is an interpretation the supreme court has historically stuck by:

The immediate effect of our copyright law is to secure a fair return for an 'author's' creative labor. But the ultimate aim is, by this incentive, to stimulate artistic creativity for the general public good.

The sole interest of the United States and the primary object in conferring the monopoly lie in the general benefits derived by the public from the labors of authors.

So if there are no fundamental rights of authors at stake here, we only need to look at the consequences. And boy, are they dumb. You can work around a license if you burn a pile of cash and carbon. It’s up to congress to decide if this waste is offset by whatever small creative work it may tenuously incentivize.

Copyrights are not intended to say no one else can economically benefit from the work. If there is a new mechanism to share or profit from a work, copyright holders are not automatically entitled to it. If the technology shifts the market such that copyright holders are no longer sufficiently incentivized to produce content, congress can consider granting new rights. But by default, rights belong to the public, since that’s who copyright law is meant to enrich: “the rights of authors are only those specifically enumerated in statute. All other rights remain with the public”

Edit: Discussion for this post on hackernews .

I’ve attempted to link to actual lawyers when possible, but some of this stuff is pretty murky. I do have some background in engineering storage systems, including ones that could theoretically be used for DVR-like systems, but have pulled everything in this post from publicly available information. I expect some of this analysis to be out of date, imprecise, or plain incorrect.

The first claim was based on the long standing MAI Systems Corp. v. Peak Computer Inc. where a copy of a program in RAM was found to be infringement. This was dismissed in Cablevision, contradicting the MAI ruling. Under the copyright act, buffering is not considered a reproduction because it is transitory. No one seemed to like the MAI ruling, so this is a good thing. It’s still unclear when a copy stops being transitory. In Cablevision, data was buffered for at most 1.2 seconds, so a conservative organization wouldn’t want to let in-memory copies sit around for longer than that.

The six services listed here average about 90 channels. No idea how to guess storage capacity because a lot of providers provide “unlimited storage”. From reading reviews of youtube live, I’m guessing they sometimes switch from recorded content to a licensed VOD model (where shared copies are fine) when you use too much storage. I’m just going to round out to 200 hours. Comcast X1 has something like 12.7 million subscribers, Youtube live TV has 3 million subscribers, Hulu live has 4, Sling has 2.3 (all from here), there are a bunch more that are under a million. There are also other major providers (AT&T, Verizon, Spectrum) I couldn’t easily find numbers for. Let’s call it 25m.

Storage systems typically store data with some redundancy, otherwise they would lose user data and suffer an outage any time a disk failed. Let’s take the storage company Backblaze as a model — they use Reed-Solomon with a 17 of 20 configuration, blowing up the storage requirement by a factor of 20/17

Backblaze gets down to $0.05/GB. This is just the HW cost for drives and servers, ignoring switches, racks, datacenter, etc.

Using Backblaze’s 2020 AFR of .93%, roughly 18,480 drives will fail per year. Assuming it takes 30 minutes to replace a drive in total, and a work year is 2,080 hours, it takes 4.43 full time employees to swap drives.

At 5.7 kWh per year per terabyte, that’s about 91 million kWh just to power the drives alone. But you’ll need networking, servers to hook those drives up to, cooling etc. Since it’s hard to figure out the overall footprint, I’m just going to assume 7 kw per rack. Staying with Backblaze’s architecture, they fit 480TiB into a 4U storage pod, so they should be able to cram 10 of those into a 42U rack. They’ll need 33,000 of those, that’s 2 billion kWh.

Using 0.000709 metric tons CO2/kWh . Using the U.S. average is probably pessimistic, since data centers often use renewable energy. Though I don’t know the overall impact of that since it can drive up the price of renewables, unless you build infrastructure for datacenters specifically. This number ignores any environmental cost of hardware manufacturing, which might be especially significant because of rare earth metals in hdd magnets.

Assuming the U.S. average of 10.68 cents/kWh

See Infringers or Innovators? Examining Copyright Liability for Cloud- Based Music Locker Services, Section 3D: Deduplication. Though deduplication was specifically upheld in Capitol Records, Inc. v. MP3tunes, LLC, it’s unclear how broadly that applies.

On television there are broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, etc) and cable networks (HBO, Cartoon Network, etc). Broadcast networks are distributed over the public airwaves through affiliate television stations and are available to anyone with a pair of rabbit ear antennas. Cable networks aren't. Cable operators (Comcast, Spectrum, etc.) negotiate to carry networks and typically carry both broadcast and cable, sent through your home through a coaxial cable. Even though the broadcast networks are available freely over the air, the cable network still needs to negotiate for a license to transmit that OTA signal over cables (this is also weird).