Does learning economics make you a jerk?

Is introductory economics an informational hazard? Teach economics as if the last 5000 years had happened.

The Economy, an introductory textbook from CORE, promises to “teach economics as if the last thirty years had happened”. For some reason, a lot of people have been writing pieces about it lately. The most important reason to care about the CORE textbook is probably the economic one: it’s free!

But, the way economics is taught governs who studies economics and how they interact with others. If a good geology textbook makes you love rocks, does a good economics textbook makes you love money? Introductory economics shapes our values, so it’s worth figuring out how textbooks choose to address or ignore this: 1

I don’t care who writes a nation’s laws—or crafts its advanced treaties—if I can write its economics textbooks

1

On an overcast day, inside a tall building, Milton can’t tell if it’s raining outside by looking through his window. Instead, he looks down at the street below. When it's raining, people use umbrellas to stay dry; so if he sees open umbrellas, it's probably raining and he should bring his own. But, for determining whether it's raining, Milton could just as well believe the converse: that umbrellas cause rain. Either theory allows Milton to predict the weather by observing the people on the street.

Call this approach “positive” — the only thing that matters about a model is how effective it is at prediction for some purpose. In The Methodology of Positive Economics, Milton Friedman distinguishes two distinct fields of study: positive economics, concerned with what is, and normative economics, concerned with what ought to be. The argument goes like this:

We can cordon off an “objective” portion of economics, positive economics, that is solely concerned with making accurate predictions about the world. Like physics or chemistry, it is independent of any ethical or normative stance. Contrast this with normative economics, which uses the predictions of positive economics to select policies with the best outcome. The task of normative economics is determining which outcomes are most desirable.

We mostly already agree about which outcomes are desirable2, so progress in economics is achieved by improving positive economics. For instance, on minimum wage, we all agree on the normative objective that everyone should achieve a living wage. The debate is only over which policy best achieves that.

The value of an economic theory is solely its predictive performance on the class of phenomena it is intended to explain. There is no problem with a theory that includes empirically untrue assumptions, “in general, the more significant the theory, the more unrealistic the assumptions”.

Friedman’s positivism had a large impact on the methodological justifications of economics. While the case that working economists uncritically use specious assumptions ignores modern economics research, introductory textbooks still frequently use the positive/normative distinction. It is a convenient way to acknowledge implausible facets of models without confronting them, so students can get on calculating.

Even the CORE textbook, which is supposed to oversimplify less, appeals to Friedman’s positive economics in the same way. And most people taking an introductory economics course will stop there. Textbook author Makinaw:

I am guided by the fact that, in introductory economics, the typical student is not a future economist but is a future voter

If an economic theory was judged on all of its predictions, umbrellas-cause-rain wouldn’t be valuable — with the causally reversed theory of rain, it's easy to make an incorrect prediction and falsify it. The causally correct theory is better at making predictions that match evidence, so the causally correct theory ought to be selected. Wrong assumptions are always able to generate some wrong predictions, so Friedman's position is more specific.

In experimental tasks, the predictions of rational choice tend not to hold up. This is fine because Friedman's positive economics instead focuses on the specific predictions the assumptions were intended to enable:

the relevant question to ask about the "assumptions" of a theory is not whether they are descriptively "realistic," for they never are, but whether they are sufficiently good approximations for the purpose in hand.

If assuming rational choice generates correct predictions about pricing widgets, it’s no big deal that it mispredicts on individual behavior we weren’t investigating to begin with.

When the purpose at hand is "should I bring an umbrella" either model of rain is sufficient. Then maybe Milton could feel comfortable teaching umbrellas-cause-rain to undergraduate students. Well except, this is bad news for the model — if it gets too popular, people might start using it for things other than our original purpose, like opening umbrellas to end droughts. And when people start using umbrellas when it's not raining, the model loses its predictive power.

Economics, however, has the opposite problem. What if adopting the model made it more true?

2

Homo Economicus, or the economic man, is the rational, self-interested, and optimizing agent that is used to model economic interactions.

Everyone admits these assumptions aren't realistic — they fail to capture many human drives, and they presume more knowledge of the world than agents can realistically attain. Less clear is how learning these assumptions effects behavior. Put another way, there is some concern that economists are assholes.

Economics students tend to free-ride more than others. Marwell and Ames instructed participants to divide an initial endowment of cash into two pools — a private pool and a public pool, which is grown and redistributed. Public pool allocation produces the globally optimal result, but individual self-interest predicts allocation to the private pool. The experimenters found that most people were robustly more cooperative than the self-interest model would predict, contributing about 50% of their endowment to the public fund. But economics graduate students given the same setup, only allocated about 20% to the public fund3.

They also asked participants what they thought a “fair” allocation to the public pool was. 3/4 of non-economists said “half” was fair, with a 1/4 that said “all” was fair. The economists… well:

Comparisons with the economics graduate students is very difficult. More than one-third of the economists either refused to answer the question regarding what is fair, or gave very complex, uncodable responses. It seems that the meaning of ‘fairness’ in this context was somewhat alien for this group. Those who did respond were much more likely to say that little or no contribution was ‘fair’. In addition, the economics graduate students were about half as likely as other subjects to indicate that they were ‘concerned with fairness’ in making their investment decision.

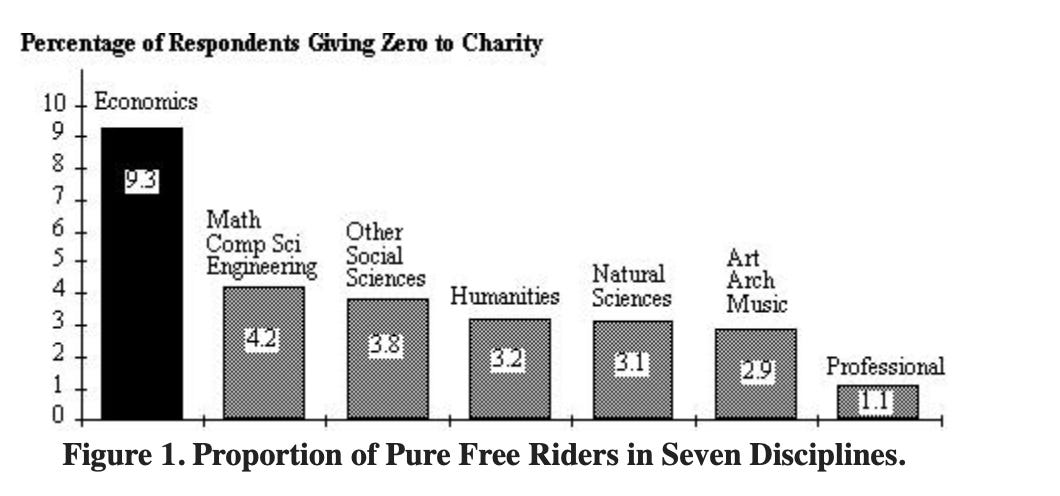

Professors of economics are twice as likely as the next field to give nothing to charity:

Though, overall charitable giving adjusted for income is only about 10% less than the broader academic population. Economics majors defect more on the prisoner’s dilemma. They give less than half as much on a solidarity game (only holds for men though?). When it’s taught by a game theorist, taking an intro econ course makes students respond more selfishly to an ethical dilemma. In a game where a lie is harmless but advantageous, business and econ majors lie more (only holds for women though?).

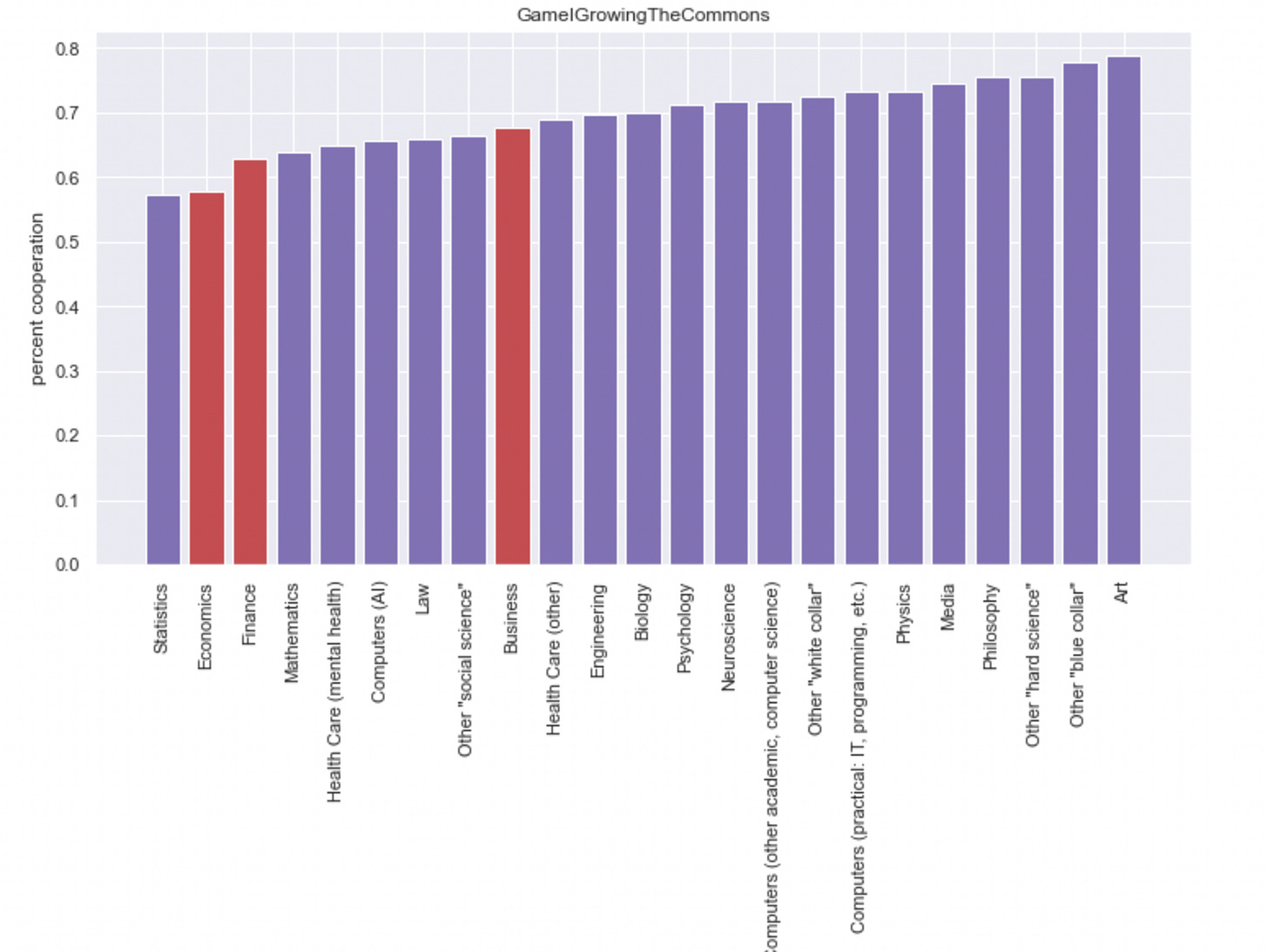

Also, in 2020, Slate Star Codex did a reader survey that included three cooperation games. It paid out by randomly selecting one of the games and a single pair of participants, and then running the game. There’s enough demographic information in the public results to do a similar analysis, though this is hugely unscientific4 (but fun).

Grouping together individuals who identify professionally with “Economics”, “Business”, or “Finance” (EBF for short), EBF professionals look somewhat more likely to free-ride in a public goods game in these results.

This doesn’t look like a result of gender bias in those fields — among just males, EBF professionals still free-ride more. In this survey the effect only applied to males (though the sample sizes are small for EBF females in the survey, 85% of respondents were male). This dataset includes a substantial number of non-students, but the effect holds for both student and non student populations.

In a few studies, the economists are selfish theory doesn’t hold. But there seems to be enough evidence that there is some robust real effect, especially in situations where outcomes the consequences of actions are highly formalized.

If economists are different, why? There are a lot of investigations into this question as well, but the answer is even less clear. Usually, two competing theories are posed:

The Selection Effect: On average, people who act selfishly are more likely to choose fields with an economics education component.

The Indoctrination Effect: Taking an economics course makes you act more selfishly.

If the indoctrination effect exists, there are a few plausible mechanisms for it. One possibility is that they directly make the student more self-interested. The other possibility is that these models make students suspicious that their peers will act with self-interest, giving them a pessimistic view of cooperation.

You can go through three decades of studies and catalog:

Whether they support ‘selfish economists’ at all

Whether they are consistent with the ‘indoctrination effect’ or the ‘selection effect’

You’ll find a lot of contradictory results, but will conclude something like :

There is some consistent measurable difference between students of economics and others in formalized interactions like business, games, and politics.

It’s unclear if it happens in messy real-world social dilemmas like “honest” behavior and charitable giving.

It’s unclear if this is the result of selection or indoctrination. Probably both.

3

Arguably, the original point of economics was to make human behavior more predictable. Cynically, it still is: People with money want to predict how other people with money act, so they can make more money. Since people with money probably know some economics, economics is the study of people who know economics5.

All economics is normative.

Why is it “easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism”? Is it surprising that students, taught to assume self-interest dominates human motivation, are unable to imagine feasible alternative systems that rely, in some part, on motivations other than the accumulation of wealth? Economics education must play some role in this. Even if you don’t want the “end of capitalism”, this inability to imagine is what makes us reconstruct scarcity for non-scarce goods, constrain use of digital information with outdated property metaphors, and build the future of human interaction for serving ads.

Economics education normalizes selfishness or selfish people choose economics. If the indoctrination effect is real, economics education erodes norms we need for coordination. If the selection effect is real, economics is, mis-selecting the uncooperative to make and advise policy. If students over-normalize self-interest, maybe we should have them read about people who… don’t do that?

In the potlatch, the host in effect challenged a guest chieftain to exceed him in his 'power' to give away or to destroy goods. If the guest did not return 100 percent on the gifts received and destroy even more wealth in a bigger and better bonfire, he and his people lost face and so his 'power' was diminished

(Except for the half-century the Canadian government banned it, “largely at the urging of missionaries and government agents who considered it ‘a worse than useless custom’ that was seen as wasteful, unproductive, and contrary to 'civilized values' of accumulation”)

Or look at Kula exchange in Papa New Guinea, the historic moral opposition to usury, the GPL, Toraja funerals in Indonesia. Or examples found in Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years, or Mauss’ The Gift. Or probably, a bunch of other works of economic anthropology. Though it’s the most appropriate place for a textbook, anthropology isn’t the only place to look. Speculative fiction is chock full of, well, speculation, on how societies could structure themselves. The CORE textbook itself appeals to the most popular post-scarcity economy of all time, though only to emphasize the importance of technological progress.

Cultural comparisons are not, as they are usually dismissed as, naïve nostalgia for pre-capitalist societies. Of course, these societies are sometimes worse in measurable ways: literacy, health, violence. But they show that self-interested action is not inevitable even at societal scales.

This is where the CORE textbook is like, almost good? Look at this section on the ultimatum game, focused on the role of norms in explaining different game outcomes among different populations. And in a footnote:

In experiments in Papua New Guinea offers of more than half of the pie were commonly rejected by Responders who preferred to receive nothing than to participate in a very unequal outcome even if it was in the Responder’s favour, or to incur the social debt of having received a large gift that might be difficult to reciprocate. The subjects were inequity averse, even if the inequality in question benefited them.

That’s not bad. This and a few other sections seem like a promising exploration of economic assumptions, including an exercise asking students to imagine life as homo economicus.

While The Economy acknowledges the roles of norms in human interaction, it immediately goes back to modeling agents as maximizers, just ones that have to take these norms into account. It treats norms as if they are static facts of the world. In this way, The Economy continues the Friedman legacy of a value-free economics. That’s why, despite questioning behavioral assumptions and emphasizing empirics, The Economy still feels pretty similar to other standard neoclassical economics textbooks.

But show me an experiment where an 18 year old reads “The Economy” and cooperates more and I’ll be pretty happy.

Paul Samuelson, who wrote a pretty popular textbook

This seems wildly wrong. But we can mostly ignore it in this essay

Though this study uses a sketchy control group (high school students), the effect holds when comparing similar students.

Some problems: the readers of SSC are very far from representative samples of college students, there is a survey response bias, SSC likely has an extreme bias in gender, political views, and economic status, all readers of SSC are more likely to have a familiarity with theories of self-interest than the average person. Though that last would work against the observed effect I would guess.

David Graeber’s Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value includes some discussion of this and the difficulty in reconciling economics and anthropology: “Economics, then, is about predicting individual behavior; anthropology, about understanding collective differences”

interesting!